Parkinson Development

Diabetes drug similar to Ozempic helped slow progression of Parkinson’s disease

In a groundbreaking development that could potentially alter the treatment landscape for Parkinson's disease, a small mid-stage trial has revealed that a diabetes drug similar to the widely popular Ozempic, known as lixisenatide, has shown promise in slowing the progression of Parkinson's disease. This finding adds a new dimension to the capabilities of a class of drugs initially designed to combat diabetes and obesity, suggesting their potential applicability in neurodegenerative diseases.

Parkinson's disease, a chronic and progressive movement disorder, affects millions worldwide. Characterized by symptoms such as tremors, stiffness, slowness of movement, and balance difficulties, the disease has long eluded treatments capable of halting its progression. Current therapies primarily focus on managing symptoms rather than addressing the underlying cause of the disease. However, the recent trial conducted by French researchers offers a glimmer of hope for a new therapeutic approach.

The trial, which spanned over a year, involved 156 participants who had been recently diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. These individuals were randomly assigned to receive either lixisenatide or a placebo, in addition to their standard Parkinson's medication. The results, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, indicated that those who received lixisenatide showed no significant progression in their motor disabilities, unlike their counterparts who received the placebo.

Lixisenatide belongs to a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. These drugs work by mimicking the action of a natural gut hormone produced after eating, which stimulates insulin release from the pancreas. This mechanism not only helps in managing blood sugar levels but also creates feelings of satiety, making these drugs effective for weight loss. The link between Parkinson's disease and type 2 diabetes, along with the potential neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists, has been a subject of interest among researchers for some time.

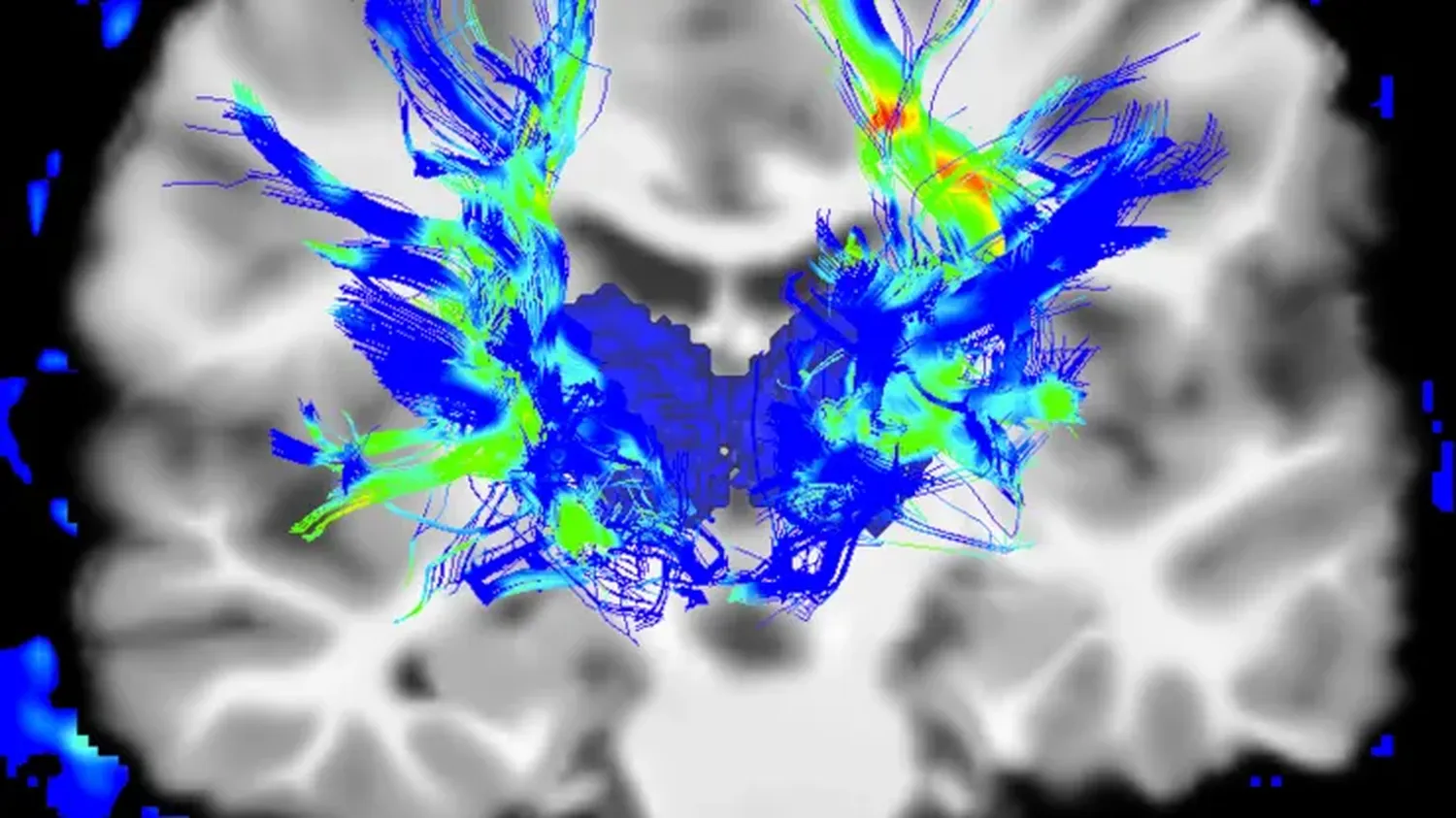

The trial's findings are particularly significant as they suggest that GLP-1 receptor agonists like lixisenatide could offer neuroprotective benefits, potentially slowing the loss of dopamine-producing neurons that is a hallmark of Parkinson's disease. This could represent a significant advancement over existing treatments, which primarily alleviate symptoms without impacting the disease's progression.

However, the trial was not without its challenges. A notable number of participants experienced side effects such as nausea and vomiting, attributed to the drug's mechanism of action. These side effects raise questions about the drug's tolerability, especially among older patients who constitute the majority of those affected by Parkinson's disease.

Despite these concerns, the trial's results have been met with cautious optimism by the scientific community. Experts have called for larger and longer studies to fully ascertain the efficacy and safety of lixisenatide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists in treating Parkinson's disease. Such studies would help determine the optimal dosage, the duration of benefits, and whether these drugs could be beneficial for patients at different stages of the disease.

The trial also underscores the potential of repurposing existing drugs to treat conditions beyond their original indications. This approach could expedite the development of new therapies for complex diseases like Parkinson's, offering hope to millions of patients and their families.

As the research community eagerly awaits further studies, the trial represents a promising step forward in the quest to find effective treatments for Parkinson's disease. With continued investigation, drugs like lixisenatide could one day play a crucial role in managing this debilitating condition, potentially improving the quality of life for those affected.